Nobody has a flawless recollection. Do you believe there was Stouffer’s Stove Top Stuffing, for example? Or that “The Berenstein Bears” were a children’s book series?

Actually, neither of these allusions is accurate. The books are really referred to as “The Berenstain Bears,” and Stouffer’s has never produced stovetop stuffing. But if you got these specifics incorrect, don’t worry; a memory research published in the year 2020 in the journal Psychological Science(opens in new tab)found that 76% of adults(opens in new tab) made at least one discernible mistake when asked to recall facts.

The research shows that a person’s memory is not perfect, even if the study’s participants’ recall accuracy was typically “extremely good,” with around “93-95% of all verifiable data” being true. Knowledge may be warped or misunderstood, and things that never happened or events that have gotten hazy through time might appear real in someone’s thinking.

This is the foundation of the “Mandela effect.”

The Mandela effect occurs when a lot of people think something happened when it actually didn’t. These groups adamantly assert their recall of an event or particular experience, despite the fact that this assertion is obviously false.

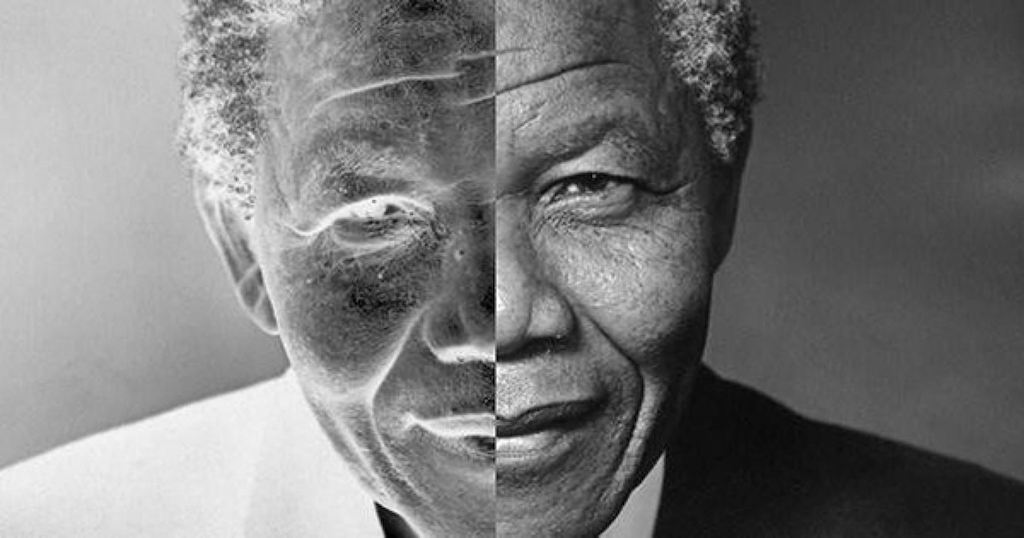

The term alludes to a widespread hoax memory in which many individuals claimed to recall Nelson Mandela’s death in custody in the 1980s. In actuality, Nelson Mandela passed away in 2013 at his house.

The phrase was created by self-described “paranormal consultant” Fiona Broome(opens in new tab) after learning that other people also remembered Mandela passing away while confined.

The Mandela effect is now used to refer to a widespread false recollection that, while being false, has taken on actual significance in the eyes of many people.

These recollections typically have a pop culture foundation. The most well-known instances of this are when individuals mistakenly recall the color of a package of a specific food flavor(opens in new tab) or think the television program “Looney Tunes”(opens in new tab) was originally named “Looney Toons.”

Why does this occur, then? Why is it that strangers might have the same misunderstanding?

Tim Hollins, a professor of experimental psychology at the University of Plymouth in the U.K., stated that “the Mandela effect seems to be strongly tied to a number of well-known memory phenomena.”

Hollins identified three similar types of memory-related phenomena: “imagination inflation,” which refers to the propensity to believe something is real the more frequently or vividly imagined, “false memory,” which is the creation of a memory that didn’t happen, “source-memory errors,” which occur when someone forgets the true source of a memory.

The “Asch conformity,” which is when people adopt a viewpoint in order to fit in with a group, and the “misinformation effect,” which describes a tendency for people’s memories to change based on subsequent learnings or experiences, are other examples of how frail our memories can be, according to Hollins.

But according to Hollins, “gist memory,” which occurs when someone has a basic notion of something but may not be able to recall the specifics, is the phenomena that most closely resembles the Mandela effect.

According to Hollins, “it is quite simple to explain how numerous persons may get to the same mistakes of recollection, even if wholly independently.” For instance, many seem to be “gist memories” that have been modified to match people’s preexisting ideas or information.

The 1940s children’s book character “Curious George” and his absence of a tail are a typical illustration of the Mandela effect.

Curious George’s tail is just a reflection of the reality that most monkeys have tails, according to Hollins. Why wouldn’t you recall him having a tail if you only remember the general idea—that it’s a monkey?

Some people who have experienced the Mandela effect, however, are sure it is proof of the existence of parallel worlds, despite the fact that there are many explanations for the phenomenon and there is evidence that our memories are not totally accurate and can change over time (opens in new tab).

According to Hollins, this is an instance of a person’s unwillingness to accept responsibility for their mistakes.

Even when confronted with the facts, Hollins observed that “people do have a tendency to over-believe their own memories.” Perhaps it’s an instance of cognitive dissonance or ego-protection.

To “explain” how individuals may simultaneously feel they have a strong memory while being presented with evidence to the contrary, Hollins claimed that people choose to believe their misplaced memory is proof of parallel universes.

Does the Mandela effect have a probability of being proof of parallel universes?

“No. It is absurd “Finally, Hollins said.